Welcome to The Merchant Life – the newsletter where over 800 of your peers get merchandising insights and an insider perspective of all things retail.

We were recently in NYC to speak at PI Apparel’s Supply Chain Forum. Liza was on stage to talk product creation and lead Q&A’s with The LNK and Another Tomorrow.

The audience was a cross-section of awesome brand leaders, merchants, and product creators.

Conversations with them supported our hypothesis of product creation processes being inherently bloated.

Lead times are increasing, product creation calendars are complicated, design teams initiate overdevelopment and more resources are continuously being sought out.

This is the kind of stuff that bogs retailers down.

We believe that product creation can be improved with a mindset of doing less instead of more.

In this edition of the newsletter, we outline the core principles of a “less is more” approach we call: Product Creation By Subtraction (PcBS).

The Six Core Principles of PcBS

1. More Supply ≠ More Demand

Every year, retailers buy into increasingly more product, driven by minimum order quantities, growth projections, and leadership directives.

This sets up unrealistic expectations of customer demand.

Seemingly, retailers believe that if they stock more products, then customers will buy more.

Yet, retail’s excess inventory repeatedly makes headlines.1 Even Nike announced that they need to make a molehill out of a mountain a.k.a. they have excess goods that must be quickly ushered out.2

At some point, even though inventories are increasing, customers don’t want to buy more sh*t – regardless of the reasons why.

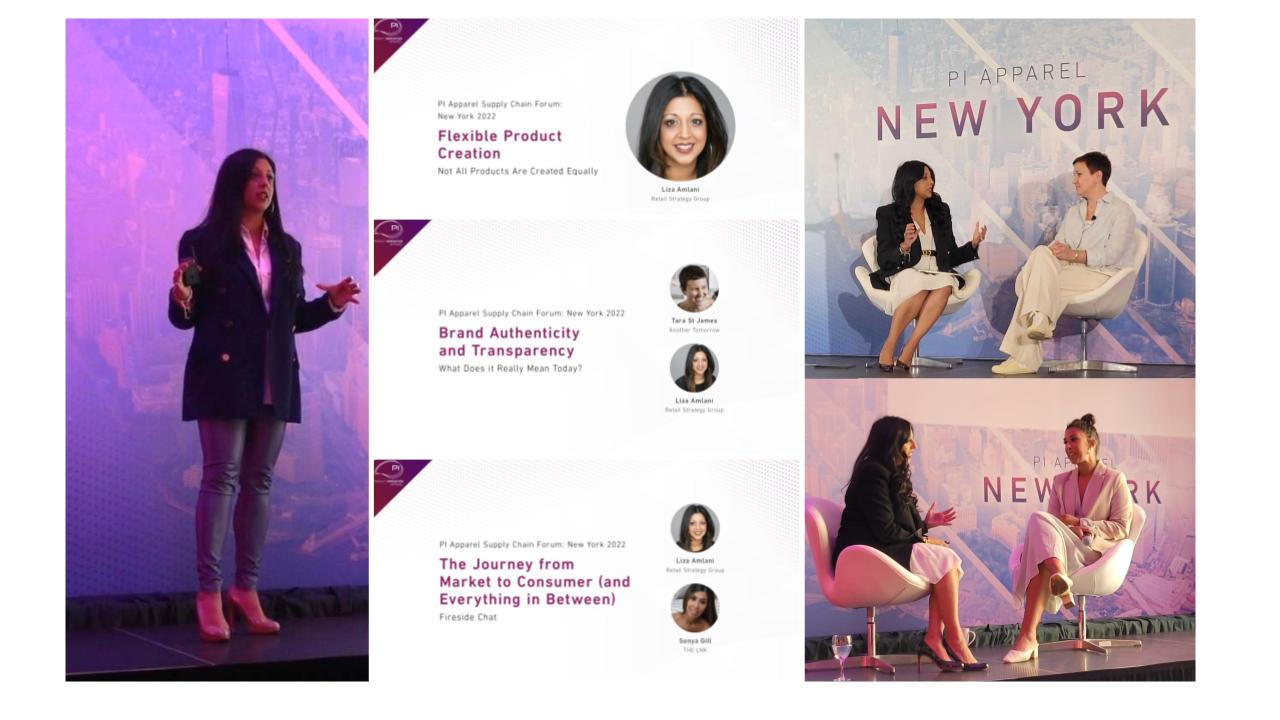

This is where the customer becomes saturated, as shown below.

Although not shown directly, customers can be turned off from buying altogether. Notice in the graph that pulling back on the amount of inventory is beneficial – moving away from saturation and into what we call the “Merchandising Sweet Spot.”

This space is where sufficient amounts of product are assorted and align with customer interest in buying. This implies that historical sales and growth projections alone cannot be the basis for seasonal planning and that SKU counts need to be re-examined.

2. SKUs Are Way Too High. You Need To Cut It.

A brand’s product assortment should have a distinct point of view.

Every product in the assortment must serve a purpose.

The purpose must tie back and support the brand’s point of view.

However, there is such a thing as being “Over-SKU’d.”

Too many products. Too many variations. The assortment has a muddled point of view.

As mentioned above, pulling back on inventory levels ensures that the customer is not saturated.

But, questioning why products exist in the assortment and possibly removing them is rare. There isn’t a strong reason to keep them aside from visual merchandising directives or simply “It’s part of our brand DNA.”

What’s necessary is to perform a SKU rationalization exercise every season.

Audit the assortment, and understand what is in it and why. Identify the top and bottom-performing products. Then, determine if bottom performers do not appeal to shoppers or if the inventory is not allocated according to consumer demand.

This is where teams need to draw upon customer insights to find some of these answers and cut SKUs accordingly.3

3. Get Cluster Un-f*cked.

Inventory is typically allocated based on store tiers, volumes, and hierarchy – this is called Store Clustering.

For example, flagships get the full assortment plus additional drops in season while smaller stores are partially assorted and get fewer drops.

The intention of clustering is to simplify inventory management.

However, this is a static approach to inventory and is out of step with the dynamic nature of the customer.

Specifically, the store inventory level may be out of sync with changes in footfall or shifts in customer shopping behavior.

If a brand reallocates in season, they quickly realize how expensive it becomes. It’s a time-consuming process and it means products have an extended absence from the shop floor.

And this contributes directly to excess inventory.

Therefore, clustering should be based on where the customer actually shops.4

Be in tune with customers, match inventory to demand, and make a dent in the excess that remains at the end of the season.

4. Acceptable Inequality

Not all products are equal.

Their materials, testing needs, seasonality, supply chains, and more…

All are unequal.

If so, then the way these products are created must also be unequal, including:

- Start/stop dates within the calendar.

- The extent of physical sampling required.

- Parties involved at key moments during creation.

Approaching product creation in a more flexible way is needed, using methods based on the complexity of each product.

In doing so, considerable time and effort is saved in the product creation process – which is either given back to teams or re-directed to a task of higher value.

Since speaking about this topic in NYC, executives from market leaders have expressed to us that this is a shift they want their own teams to make.5

5. Value Added Product Creation (VAPC)

VAPC follows naturally from Acceptable Inequality.

We define it as follows:

If you don’t add value to a product during its creation process, don’t touch it.

Let’s explain.

Product creation calendars are constructed as a “work-back.”

Meaning, a goal is set and teams work backward from said goal to construct a plan to get there.

These goals are called “key alignment moments (KAMs)” where teams meet for reviews and approvals.

The question is, do ALL functions within product creation need to be involved at EVERY key step for ALL products?

Absolutely not.

The seasonless, core t-shirt brought back every season doesn’t need input from fit, testing, sourcing, and sampling. Teams representing those functions DON’T add value at key steps – cut their involvement.

The innovative, technical jacket is the opposite where fit, testing, sourcing, and sampling are required. Teams with those functions DO add tremendous value at key steps – make sure they are involved.

This “trimming of fat” helps to uncover redundant steps, assign clear accountability, and helps teams know exactly what to work on and when.

6. Curb Your (Design) Enthusiasm

Design-led brands allow design teams to work without constraints as so not to limit their creativity.

However, this directly impacts the efficiency of product creation and time to market.

For example, design has chosen a specific material seen at a trade show for a product design. This kickstarts a chase where material development works with sourcing, costing, and factory partners on this request.

This could end up as a drawn-out process if no solution is produced. Design may ask for further development cycles, pushing out deadlines and producing low adoption rates of materials.

Instead, the following is needed:

- A limited number of new developments design can request each season.

- Adopting the mindset of designing into already available materials in a pre-approved library.

- Track material adoption rates and install accountabilities for unnecessary overdevelopment.

- A neutral party watching over the product creation calendar, ensuring deadline adherence.6

As for limiting the creativity of the design team…contrary to popular belief, constraints in fact enable creativity – research demonstrates how teams with reduced resources are able to use what’s in hand in unexpectedly positive ways.7

Closing Comments

A common thing that we hear when talking to brands and retailers:

“We’re using best practices in our approach to product creation.”

Now, best practice sounds pretty good.

Until we recognize that this is the not-so-distant cousin of the familiar:

“We’ve always done it this way.”

The translation is:

“We’re stuck.”

In a specific way of being, working, acting, and doing.

Best practices have been working fairly well for years.

But, it’s not the way to raise the bar.

Better practices are required today to be, work, act and do – better.

In the case of product creation, better is achieved by doing less.