Welcome to The Merchant Life, for retailers and retail enthusiasts wanting the insider perspective of all things retail.

Now let’s talk shop.

In this week’s newsletter, we talk about the impacts of globalization in retail from sourcing, manufacturing, supply chain and logistics.

Now think back to the last time you were driving to work and get this started…

Whatever Floats Your Boat

Oh so long ago…when commuting to work was a thing. 🤔

Imagine driving along the freeway and coming to a standstill because there’s a 5 car pile up on the road ahead.

You’re already late for work.

The frustration.

The angst.

Well, take that feeling and multiply it by a factor of 59 billion and you get an idea of how impactful the news about a ship being stuck in the Suez Canal is.

It was stuck for 6 days, 3 hours and 38 minutes, costing $400M/hour, at approximately $10B/day.

Thankfully, that ship has finally sailed.

Now to clear the backlog…well that could take days.

A crisis like this and many other disruptors come with a cost.

The question is, is the risk of relying on global suppliers and manufacturers really worth your time and money?

Supply Chain in Crisis

Aside from giving supply chain experts a heart attack, the Suez Canal crisis gave us the best memes since Bernie’s gloves at the inauguration.

The crisis also gave said experts a run for their money, shifting the conversation from last-mile and BOPIS to ships at sea.

Global supply chain disruptions like the pandemic, the Xinjiang cotton ban, and Brexit will continue to wreck havoc until something gives.

But really, what gives?

To start, most companies rely on international trade.

From cotton cloth production in China, silk in India, manufacturing and production in Bangladesh and the EU – you are putting all your eggs in one basket.

An overseas basket – far away from your headquarters, distribution centre, and (more importantly) your customer.

Depending heavily on global supply chains to source, produce, manufacture, and move your product can be very risky – especially if a piece of the puzzle breaks down. Moreover, companies outsource different parts of their supply chain, which end up managed by 3rd parties with outdated processes and a lack of transparency.

When sh!t finally hits the fan, how can you really manage the crisis?

We spoke to Gary Newbury, a supply chain and last-mile expert, on why having a global supply chain has become a problem.

“Generally speaking, over the last thirty years, countries, businesses and ultimately consumers have benefitted from geographically extended supply chains, focused on container loads of products being manufactured in and around low labour cost regimes in the Far East, imported and feed through domestic retail distribution networks.”

So going global is great right?

Not really and definitely not for everyone.

“This has benefited both local economies and helped countries like China to develop into formidable economic powers. However, we have seen this focus on “lowest possible element cost” has created, in itself, a focus on shortcuts and mediocre quality in products and how we approach how we do things where overproduction, over consumption and stock outs are now deeply embedded into our thinking.”

From a merchant perspective, a global supply chain offers more choice than a homegrown local operation.

A few benefits:

- More choice of suppliers

- More choice of raw materials

- Lower cost prices

- Lower labour and production costs

- More access to specialized skillsets

Let’s face it. You get more bang for your buck.

Not so fast. There’s a cost to be paid for these benefits.

The fact remains that it is much cheaper to source, manufacture, and produce goods in countries that have a monopoly on the retail trade.

It may not be the best quality, it may take much longer to get to your DC, and it may get stuck at sea BUT does it really matter?

Going Local. Is it Loco?

As you localize parts of your supply chain, your suppliers, your manufacturing and production, you minimize your risk of delays. You have visibility to your product development journey as your teams are onshore.

This can impact your timelines.

You can get to market faster and keep up with customer demands. As demand shifts to more loungewear, you can invest in these categories, put more open-to-buy into the product that is selling, and deliver to the customer faster.

When the pandemic hit and many hospitals were out of PPE, local designers and manufacturers shifted gears and switched their production facilities to cater to demand.

Localizing your supply chain will enable you to be more flexible and adaptable to technology advancements. Digitizing and automating warehouses and upgrading logistics will help you get FASTER to market.

Adding predictive analytics to your demand planning will help you get the RIGHT PRODUCT to the customer at the RIGHT TIME. The closer you are to your suppliers, the more you can work together to digitize and become ‘smart’ together, allowing you to service the customer in real-time.

The grocery and cannabis industries, for example, have shifted to local growers and suppliers, giving them the advantage to supply product when needed.

Closer is better. Or is it crazy?

The Balancing Act

Although localization is an attractive options, we have to consider these drawbacks:

- Less choice of tradespeople, artisans, skillsets, and producers onshore vs. overseas.

- High costs to manufacture compared to the Far East.

- Many raw materials are not produced locally.

- Local infrastructure does not exist.

Balancing your supply chain and implementing a hybrid model could be a way to go.

Cotton is the world’s most widely used natural fibre but it is not grown in Canada.

This means we can localize the entire supply chain in Canada that uses cotton, except for the actual cotton.

If we were to import the cotton, we could produce garments locally which would give us a hybrid model.

Gary puts it like this:

“A more careful and strategic review of where within the value chain each element needs to be positioned is required. This clearly points to a situation where The Far East will still be essential to some categories for raw materials, but assembly, customization and other value-added services would be better based domestically to respond more efficiently to changes in consumer sentiment.”

In essence, a blended approach would be ideal where we could source raw material globally and process locally.

Let’s follow the money with that approach and see where it leads us.

Profits Win.

We are in retail to make a profit.

There’s nothing wrong with that.

In turn, companies can make a positive impact in other areas like social justice and sustainability as they become successful (if they consciously choose to do so).

Following the money will show you that gross margins and profits drive companies to factories where they can negotiate the lowest cost, increase their production to drive more sales.

Imran Ahmed wrote a piece for The New York Times in December 2020, an article titled: “How Can a Garment Be Cheaper Than a Sandwich?”

“Take Bangladesh, which is home to four million garment workers. Many of them earn little more than the government-mandated minimum wage: only 8,000 taka, or less than $100, per month. Fair-wage campaigners say that double the amount would be needed for workers to live comfortably.”

In fact, many garment workers are not being paid at all. BOF published an article on March 11 (of this year!) talking about wage theft:

“A new investigation into wage theft among garment workers covering eight factories that supply 16 major international fashion brands has uncovered 9,843 workers who are fighting to have their wages and legally-owed benefits paid, according to the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC).

The factories in questions were located in Cambodia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Bangladesh and Ethiopia, and supplied brands including Carter’s, Hanes, H&M, Levi Strauss & Co., Lidl, L Brands, Matalan, Mark’s Work Wearhouse, Next, New Look, Nike, PVH, River Island, Sainsbury’s, s.Oliver and The Children’s Place.”

The 16 brands named in the report had a combined profit of $10B in the 2nd half of 2020.

That’s right.

$10,000,000,000.

Garment workers that barely made $100 a month, making product for major international fashion brands WERE NOT PAID.

Doing the math will make your head spin but if you were told to shift to a local supply chain and make your goods locally in Canada, the average salary per hour for a factory worker is $15.64.

Add all your material costs, labour costs, etc. and the total figure starts to climb rapidly.

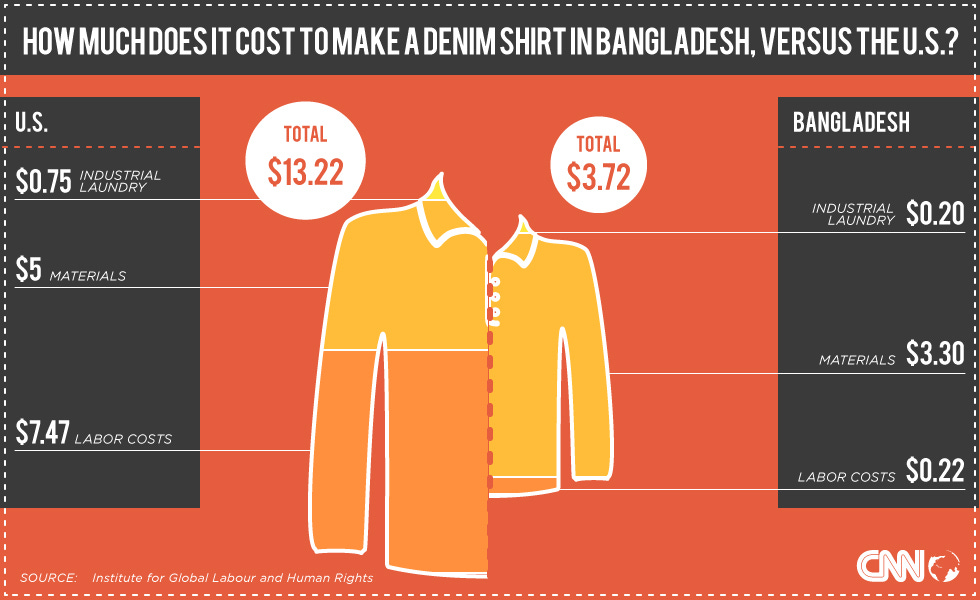

CNN posted this after the Rana Plaza garment factory collapsed in May 2013. Besides the current labour costs, not much else has changed in terms of the cost model outlined below.

As a merchant, my mark-up on a private label program was between 70% and 80%, depending on the country I was working in.

The global supply chain is much more profitable and its operation is deeply embedded in the modus operandi of the retail world.

A disruption like Ever Given in the Suez Canal is par for the course – an event in time that will pass. Consider that product delivery windows are 3 months for a reason. They give the supplier time to deliver in case of disruption.

Retailers need to decide what’s important to them and build out their supply chains accordingly.

The bottom line generally wins.

RSG Insights – My Merchant Life

I spent some time as a Buyer and Product Developer for CABAN stores, part of the Club Monaco umbrella.

Many brands I bought were manufactured globally.

I also developed a few private label programs, trickling in higher margin product throughout the assortment.

One Fall season, I was developing a men’s and women’s cashmere program.

We found a local Canadian designer and manufacturer who we worked with to develop the program. Choosing local allowed me to be more hands-on, keep an eye on the quality of the fabric, be part of fitting sessions, and ‘drop’ in when I could! It was an experience I had never had before because I had never been able to buy a brand that was made locally.

I sold out of key items in season and was able to order more. Not only did working with a local vendor/supplier allow me to get to market faster, but we developed a great relationship so that I could work with them again.

A few things I didn’t have to worry about:

- Managing a production and delivery timeline of placing a reorder.

- Waiting for a container to be full before shipping the product from overseas.

- Paying to air product because the collection was made locally.

Keeping production local helped me make better margins and have a great private label success story.

There are many advantages to onshoring/nearshoring but it has to make sense for the right product categories and for the business.

The opportunity to localize doesn’t come along that often but when it does, you should absolutely take advantage of it.

If the price is right.