If there ever was a case for process innovation, the recent hubbub around the football Hall of Fame is Exhibit A.

For a moment, the whole world seemed to unite in disbelief that Bill Belichick won’t be a first-ballot Hall of Famer.

Whether that’s because of scandals like Spygate, voter jealousy, or plain old hurt feelings is one side of the equation.

Another issue people have pointed out: the voting process itself is flawed. It’s built in a way that makes a bizarre outcome like this possible.

But that’s not the only headline-worthy example of why process innovation matters.

I present to you, Exhibit B: Lululemon and their Get Low leggings.

We don’t need to rehash the full “Get Low-gate” story here, it’s been covered plenty elsewhere.

What we do want to focus on is fit. The notable part (to us, at least) was that because the leggings were see-through, the guidance was to size up. That meant the brand also had to update the relevant sizing and fit info accordingly.

And you can probably imagine the return volume that followed.

Incorrect sizing is the #1 reason apparel gets returned.

The sheer volume and dollar value of returns is still a major cost for retailers and brands.

Naturally this leads to conversations about solutions for returns, reverse logistics, and tech options. B

ut here’s the thing: fit is a process problem first.

Most brands try to solve fit at the exact moment it becomes the most expensive to fix:

At proto review.

This is where the line is already committed, the fabric has already been chosen and when the factory is cutting patterns.

If you want fewer returns, fewer markdowns, and fewer customers quietly switching brands, you need a fit process that runs ahead of the calendar rather than behind it.

Here’s how:

1) Move fit upstream.

- Start earlier than proto review.

- Define fit intent during line planning.

- Standardize fit intent language (slim, comfort, relaxed, body con, oversized) so teams stop translating.

- Partner with materials early so the fabric supports the fit intent.

Make fit intent and fabric decisions together.

2) Build fit criteria and tolerances into the system.

- Lock the right block for the fit intent. No freestyle pattern changes every season.

- Set tolerances by fabric type so a spec is actually meaningful.

- Fit beyond the base size for new silhouettes (at least the ends, not just the middle) to avoid curve surprises.

- Fit tests should include: fit intent, silhouette and drape check, range of motion testing (especially for performance brands), chafe and irritation, moisture and thermal, component performance, durability, and wear testing.

A base size can look “fine,” and a size curve will still fail.

3) Close the feedback loop

- Re-evaluate fit blocks and grade rules regularly using fit-related feedback and complaints.

- Dissect returns data like a merchant. Figure out where is the garment tight? Where is it long or short? Which sizes fail and on what body shapes?

Customers are not static. Your fit blocks cannot be either.

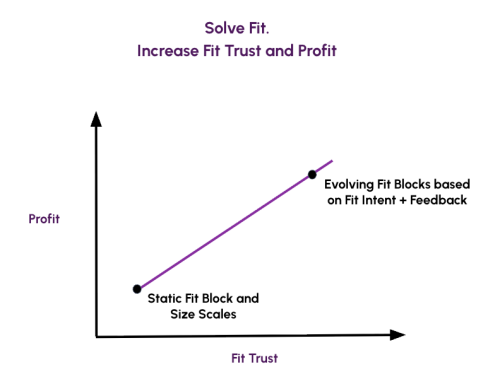

If you can get closer to solving fit, you prevent returns and markdowns.

Now you are no longer talking the language of mitigation to handle returns. And you earn something even more valuable: Fit Trust.

When customers trust your fit, they come back and want to buy at full price.

The diagram below makes the lesson even clearer.

Those tips might help fix a bunch of fit issues with apparel.

However, fitting Belichick into the Hall of Fame is a fit issue that we can’t help with.

Someone else smarter than us needs to get on that one.